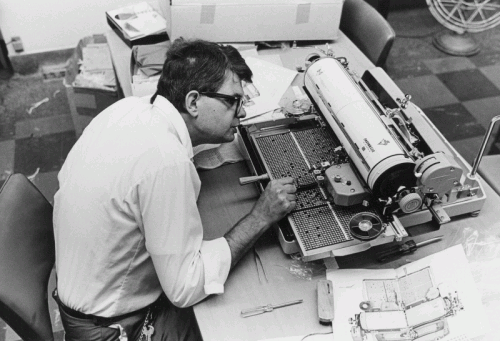

The most agonizingly complex language that I’ve ever tried to learn is OT Hebrew, which (among other challenges) expresses vowel intonations through a vast variety of tick marks, jots, and tittles surrounding the consonants. These are not constant; rather, the meaning of the different markings varies depending upon the order of the letter within the word, order within the syllable, the nature of the preceding consonant and the following consonant, and all possible combinations thereof. But I gather that Hebrew is comparatively simple to Mandarin. As a necessary result of that complexity, Mandarin typewriters are sophisticated machines:

As you can see, the typewriter is extremely complicated and cumbersome. The main tray — which is like a typesetter’s font of lead type — has about two thousand of the most frequent characters. Two thousand characters are not nearly enough for literary and scholarly purposes, so there are also a number of supplementary trays from which less frequent characters may be retrieved when necessary. What is even more intimidating about a Chinese typewriter is that the characters as seen by the typist are backwards and upside down! Add to this challenging orientation the fact that the pieces of type are tiny and all of a single metallic shade, it becomes a maddening task to find the right character. But that is not all, since there is also the problem of the principle (or lack thereof) upon which the characters are ordered in the tray. By radical? By total stroke count? Both of these methods would result in numerous characters under the same heading. By rough frequency? By telegraph code? Unfortunately, nobody seems to have thought to use the easiest and most user-friendly method of arranging the characters according to their pronunciation.

Link via Geekosystem | Photo: Victor Mair

Original post:

Chinese Typewriters